by Nomad

If the War on Drugs has been a failure, it's time to ask what exactly went wrong. That's a question we will be taking a closer look at next week.

If the War on Drugs has been a failure, it's time to ask what exactly went wrong. That's a question we will be taking a closer look at next week.

Firstly, in this post, we will look at the scale of the problem.

The noted economist, Milton Friedman, once remarked:

Still there is a tiny kernel of truth buried in the idea.

There are seven times as many citizens in prison in the US than any other developed country.

There are seven times as many citizens in prison in the US than any other developed country.

The land of the free has become the land of the imprisoned drug offenders and the home of the brave has somehow become a nation scared to death of a SWAT team kicking down their doors.

Even so, the drug problem continues to destroy lives.

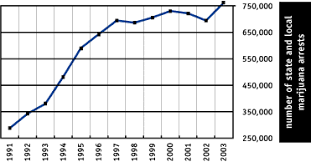

The graph on the right shows how cannabis arrests have soared over the decades. Yet, according to most scientists, cannabis was a drug that was certainly no dangerous than alcohol and arguably less harmful than cigarettes.

However, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, white and black people report using drugs at similar rates.

However, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, white and black people report using drugs at similar rates.

Another way to see those trends: Incarceration for drug activity is perhaps becoming a little more democratic.

I'm in favor of legalizing drugs. According to my values system, if people want to kill themselves, they have every right to do so. Most of the harm that comes from drugs is because they are illegal.

Of course, Friedman ignores the very serious consequences of drug addiction, such as wasted lives and destroyed families, the increase in crime and poverty. and generations of young people who might have contributed to society being turned into veritable zombies. Doing nothing, no matter what Uncle Milt might thing is not an viable option. In that light, Friedman's notions strikes one as being cold and pitiless.

Still there is a tiny kernel of truth buried in the idea.

If wars are ever moral in any sense, the War on Drugs was depicted in its opening salvos, as a battle of good against the evils of addiction. In fighting this particular war, however, one of the problems was understanding exactly who the enemy was and who were its victims.

Of course, it was clear something had to be done. However, at some point after President Nixon officially kicked off the War on Drugs in 1971, the anti-drug policy jumped the tracks and then coasted along with nobody at the wheel.

Today after four decades of fighting, the drug war has, at least according to one source, cost the taxpayers over $1 trillion dollars.

Aside from financial aspects of the war on drugs, another concern was its negative impact on the civil liberties of all Americans. That was true even those who would never have dreamed of snorting, dropping, shooting or lighting up any illegal substance.

The US government, at some point, moved from attempting to help addicts and finding and punishing dealers to simply locking nearly everybody in prison.

Drug convictions went from 15 inmates per 100,000 adults in 1980 to 148 in 1996, an almost tenfold increase. More than half of America's federal inmates today are in prison on drug convictions. In 2009 alone, 1.66 million Americans were arrested on drug charges, more than were arrested on assault or larceny charges. And 4 of 5 of those arrests were simply for possession.

There are seven times as many citizens in prison in the US than any other developed country.

There are seven times as many citizens in prison in the US than any other developed country. The land of the free has become the land of the imprisoned drug offenders and the home of the brave has somehow become a nation scared to death of a SWAT team kicking down their doors.

Even so, the drug problem continues to destroy lives.

According to a 2014 report by Human Rights Watch, backs up the earlier Time article. That report concludes that Reagan's "tough-on-crime" laws have filled U.S. prisons with mostly nonviolent offenders. In 1980, when Reagan took office, the United States had 50,000 people behind bars for drug law violations – today we have more than half a million.

One reason for the sharp rise has been that marijuana- a drug that nearly half of the population say they've tried at one time in their lives- was considered as dangerous -and as criminal- as crack cocaine or heroin.

There was a good reason for this. Both Nixon and Reagan refused to consider any kind of distinction between illegal drugs. It was, after all, a moral issue and winning the war required determination and not useless debate.

There was a good reason for this. Both Nixon and Reagan refused to consider any kind of distinction between illegal drugs. It was, after all, a moral issue and winning the war required determination and not useless debate.

And so, the relatively harmless cannabis which, as a weed, could be cultivated nearly any place- including inside US borders- became the weakest link in the campaign against illegal drugs.

The graph on the right shows how cannabis arrests have soared over the decades. Yet, according to most scientists, cannabis was a drug that was certainly no dangerous than alcohol and arguably less harmful than cigarettes.

In the wider view, America's anti-drug policy has undermined human rights and due process in a number of ways. For example, under the hard-line policies of the Reagan era, the whole question of constitutional protection against "unreasonable search and seizure" became much more of a grey area.

Before the Bush administration launched its equally defective and desultory war on terrorism, the war on illegal drugs provided the more or less plausible excuse for the militarization of local law enforcement.

But there's more. There's been another corrosive side effect of the War on Drugs. By failing to provide oversight on law enforcement, there's been a emphasis, critics claim, on the targeting of blacks and minorities.

This in turn has exacerbated the nation's racial problems.

Was it discrimination, or unfair profiling or did it simply reflect the actual drug use among minorities? That depends on whom you ask.

Was it discrimination, or unfair profiling or did it simply reflect the actual drug use among minorities? That depends on whom you ask.

Yet, a 2009 report from Human Rights Watch found that black people were much more likely to be arrested for drugs. In 2007, black people were 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for drugs than white people.

Interestingly, that may be changing but that doesn't necessarily spell good news.

According to a 2009 study "The Changing Racial Dynamics of the War on Drugs" by The Sentencing Project, for the first time in 25 years the number of African Americans incarcerated in state prisons for drug offenses has declined substantially.

That fact could be a little deceptive though. While there has been a 21. 6 % drop in the number of blacks incarcerated for a drug offense during the period 1999-2005, there's also been a corresponding rise in the number of whites. (The number of Latinos incarcerated for state drug offenses was virtually unchanged.)

Another way to see those trends: Incarceration for drug activity is perhaps becoming a little more democratic.

The number of drug offenders in state prisons of all races and ethnic backgrounds declined if only because so many of the state and federal prisons are now full.

The War on Drugs has been a case in which the cure was- if not worse then- almost as bad, than the problem itself.

This is one reason for the constructive re-think of the policy of incarceration over prevention and treatment.

In a series of posts in the coming week, we will take a look at what went wrong. We will look at the origins of the crusade, the Nixon's rationale, Ford's ironic surprise and Jimmy Carter failed attempt to add common sense to the policy.

We shall then wrap it all up with the most the most preposterous and disturbing strategy that turned the American public against the crusade. How, in their zeal to stamp out drugs, Reagan officials lost the once-solid support of the American public, by making everybody into a suspected drug criminal.

Here's is a related article from NewsWeek, reposted with permission.