by Nomad

The story of the Lawrence Mill Strike of 1912 has - like most of the history of the labor movement- received very little coverage in the mainstream media.

With that in mind, I offer this summary of the events that occurred over one hundred years ago in the mill town of Lawrence, Massachusetts.

History always provides both interesting parallels and contrasts to our own age. Before we look back, therefore, let's take a quick examination at our own times as a kind of reference.

Today worker wages have remained stagnant since the 1980s. while hourly productivity has risen to all-time high levels. The reason generally cited to justify this effect is the increased competition from third world manufacturing with low-income workers in countries such as China and India. As CNN reported back in 2011,

Today worker wages have remained stagnant since the 1980s. while hourly productivity has risen to all-time high levels. The reason generally cited to justify this effect is the increased competition from third world manufacturing with low-income workers in countries such as China and India. As CNN reported back in 2011,

Our Gilded Age

Incomes for 90% of Americans have been stuck in neutral, and it's not just because of the Great Recession. Middle-class incomes have been stagnant for at least a generation, while the wealthiest tier has surged ahead at lighting speed... Meanwhile, the richest 1% of Americans -- those making $380,000 or more -- have seen their incomes grow 33% over the last 20 years, leaving average Americans in the dust.

For corporations and the super-wealthy, this has meant boom times- even during the recession. The rich have gotten richer, but a whole lot richer. The working class, however, has seen a steady deterioration in their standard of living. The trickle-down hasn't trickled.

According to Harvard magazine:

The United States is becoming even more unequal as income becomes more concentrated among the most affluent Americans. Income inequality has been rising since the late 1970s, and now rests at a level not seen since the Gilded Age—roughly 1870 to 1900, a period in U.S. history defined by the contrast between the excesses of the super-rich and the squalor of the poor.

And same CNN article cited above gives us one reason for the problem:

One major pull on the working man was the decline of unions and other labor protections, said Bill Rodgers, a former chief economist for the Labor Department, now a professor at Rutgers University.Because of deals struck through collective bargaining, union workers have traditionally earned 15% to 20% more than their non-union counterparts, Rodgers said.But union membership has declined rapidly over the past 30 years. In 1983, union workers made up about 20% of the workforce. In 2010, they represented less than 12%."The erosion of collective bargaining is a key factor to explain why low-wage workers and middle income workers have seen their wages not stay up with inflation," Rodgers said.Without collective bargaining pushing up wages, especially for blue-collar work -- average incomes have stagnated.

One hundred years ago, the textile mills in New England -which was the starting point for the industrial revolution in the US were in a similar position. The strength of labor unions- to bring about better social conditions for workers was still in its infancy. The labor action in Lawrence was to be a major test of might against might.

The Stage of History is Set

If any one industry came to represent the industrial age it would probably be the textile industry. With its looms, its workers and the mill owners and the capitalists that profited from the industry, it was where the industrial revolution really began. In the United States, that new age started in the mill towns of Massachusetts back in the 1830s. By the turn of the new century, after seventy or so years, the industrial revolution had matured into something we might recognize today.

According to the book about the strike, The Trial of a New Society, despite consolidations of mills, legislative tariffs to protect their industry and improved machinery to boost production, the wages and conditions of the textile workers remained unchanged. In fact, the wages for mill workers were in a steady decline. According to the census figures from 1890 to 1905, wages had actually decreased by 22% to 19.5%.

One reason for the conditions was the stiff competition from Europe's low-wage economies. American mills simply could not keep up and were forced to increase production and cut wages. The number of looms had increased but the number of workers had not. For the textile industry, these were boom years. For their employees, it could hardly be much worse.

As one source notes:

Working conditions became unbearable. Social reformers documented the high mortality rate due to malnutrition, overwork and occupational illness.

A report at that time found that for the month of November 1911, the 22,000 textile workers in Lawrence, received an average of $8.76 per week. That average was for a good week only and included the wages to all grades of labor. Almost one-third of the workforce earned less than $7. (Critics of that study thought even those numbers were exaggerated and that the figure was much closer to $6 a week.)

The fix was in, workers well understood. Survival came at a cost. For example, the rents in Lawrence were, on average higher than in New York, Chicago or Boston, without any of the social advantages of the big city.

The mill workers claimed that over 50 percent of the workforce in Lawrence made up of women and children which added to the burden on family life for the mill workers. The workers were mostly Pole, Lithuanian, Russian, Irish and Italian immigrants- all willing to work at whatever wage they could find.

Or so the mill operators had long thought.

Clearly, something had to give. Previous labor actions had failed and the long-standing grievances had been ignored by the mill operators.

A crisis was building and, on January 11 1912, the final blow came when women workers of the Everett Cotton Mills in Lawrence, received their pay envelopes and found they had been short-changed by 32 cents. (Nothing for us, perhaps, but in that day, it would have bought three loaves of bread for working families whose wages were well below the poverty line.)

The reason for the pay cut was a new state law which, ironically had been considered the answer to the long hours. This law had just come into effect the week before and workers were extremely nervous about how the mill would apply the provisions of the law that reduced the work week by two hours.

To help alleviate the distress, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law, effective Jan. 1, 1912, that reduced the workweek for women and children to 54 hours from 56. Lawmakers didn't anticipate that the mill owners would respond by cutting wages by 4 percent.

Although the wage reduction was small in amount, the workers of Lawrence realized from experience that the new wages would not be sufficient to live on.

Their position... was near enough to absolute starvation as to leave no doubt on that point. So rather than suffer a further weekly loss of six loaves of bread, a great part rose up en masses in spontaneous revolt.

As news of the short-changed wages spread throughout the factory, women began turning off their looms and walked out. The next day, workers at other factories joined them. Soon, some 25,000 workers were on strike. Every mill in Lawrence was closed down as a result of the labor action.

The events of Lawrence were to send shivers down the industrialized world.

Lawrence, with its exploitation and luxury for the benefit of a few capitalists on one side, and its slavery and starvation for the many workers on the other, was now enacting the worldwide drama of the class struggle- of the irrepressible conflict between capital and labor.

United

Men, women and children workers joined together in the revolt. It was one issue that encouraged true gender equality- a rarity in that age. As one source explains:Women didn’t shy away from the protests. They delivered fiery rally speeches and marched in picket lines and parades. The banners they carried demanding both living wages and dignity—“We want bread, and roses, too”—gave the work stoppage its name, the Bread and Roses Strike.

Furthermore, the strike united the various nationalities within the labor force.

Although strikers lacked common cultures and languages, they remained united in a common cause. The social networks of the day—soup kitchens, ethnic organizations, community halls—stitched the patchwork of strikers together. And once news of the walkout went viral in newspapers around the country, American laborers took up collections for the strikers and local farmers arrived with food donations.

On the other side of the battle lines, the industrialists and political leaders joined together to put down the revolt. One common method to undermine the legitimacy of any strike is to plant provocateurs among the strikers. Even so, the feelings among the strikers were riding high and violence was always a possibility.

Mill owners and city leaders hired men to foment trouble and even planted dynamite in an attempt to discredit strikers. Lawrence’s simmering cauldron finally bubbled over on January 29, when a mob of strikers attacked a streetcar carrying workers who didn’t honor the picket line. That afternoon, as police battled strikers, an errant gunshot struck and killed Anna LoPizzo. The following day, 18-year-old John Ramey died after being stabbed in the shoulder by a soldier’s bayonet.

The Exodus of the Children

In the following month, as the tension increased, the children of the strikers- 119 in all- were sent to New York to be sheltered by relatives or, in some cases, volunteer families. Most of these children, it was discovered, were suffering from malnutrition.

In terms of publicity "children's exodus" was a stroke of brilliance. When the children arrived in Manhattan, a cheering crowd was there to greet them at Grand Central Station. Another trainload arrived the following week.

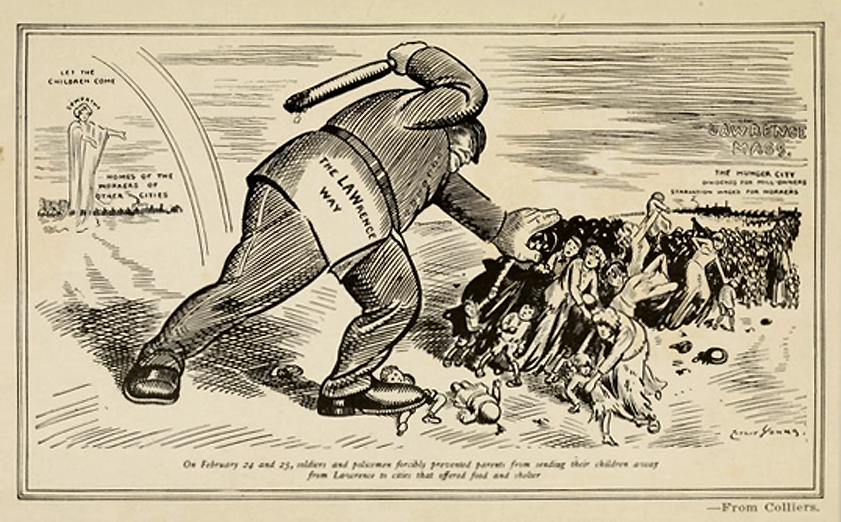

When Lawrence authorities, realizing they were losing the public relations battle, attempted to halt 46 children bound for Philadelphia, things went from bad to worse. At the train station, the city marshal ordered the families to disperse and take their children home.

When defiant mothers still tried to get their children aboard the train and resisted the authorities, police dragged them by the hair, beat them with clubs and arrested them as their horrified children looked on in tears.

The Public Takes Notice

Gradually, with the help of labor-friendly newspapers, the tide of public opinion was changing in support of the workers. Across the nation, the support continued to grow for the strikers. President Taft ordered his attorney general to investigate, and Congress conducted a hearing on the strike on March 2.

Testimony at those hearings from child workers age 14 or younger gave vivid descriptions of the working conditions and the pay inequities. Revelations from the hearings appalled the nation.

A third of mill workers, whose life expectancy was less than 40 years, died within a decade of taking their jobs. If death didn’t come slowly through respiratory infections such as pneumonia or tuberculosis from inhaling dust and lint, it could come swiftly in workplace accidents that took lives and limbs. Fourteen-year-old Carmela Teoli shocked lawmakers by recounting how a mill machine had torn off her scalp and left her hospitalized for seven months.

This turned out to be the final blow for the textile factory owners. Once the public became aware of the shocking conditions, the strikers had won. The capitalists quickly realized they had lost the battle of public opinion and any further resistance was pointless.

By the middle of March- nine weeks after the strike had begun- the mill owners and worker union representatives agreed to a 15 percent wage hike, an increase in overtime pay and amnesty for strikers.

On March 14, the strike was officially over.

However, the Bread and Roses Strike was a victory not merely for the workers in Lawrence. That same month, 275,000 New England textile workers received similar raises and workers in other industries had reason to hope for changes too.

Reflections on Today

The days of the great labor unions seem long gone but the conditions that gave rise to them still remain with us, here and all over the world. Fortunately, the work conditions have improved in the US for workers in general., However, the same cannot be said for the workers in other countries- countries that American workers must compete with.

A Bangladeshi or Sri Lankan woman or a child worker in India, Vietnam, Indonesia or Brazil would have a lot in common with the Lawrence mill worker of 1911. Instead of raising the working standards for these countries, American workers are somehow expected, as part of globalization, to return to the days before the "Bread and Roses."

* * *

The Lawrence events is often called "The Bread and Roses Strike." In fact, the name originated from a poem, which appeared a year before the labor action began, published in American Magazine and written by James Oppenheim. Here are the words:

Bread and Roses

As we come marching, marching in the beauty of the day, A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray, Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses, For the people hear us singing: “Bread and roses! Bread and roses!” As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men, For they are women’s children, and we mother them again. Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes; Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses! As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead Go crying through our singing their ancient cry for bread. Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew. Yes, it is bread we fight for — but we fight for roses, too! As we come marching, marching, we bring the greater days. The rising of the women means the rising of the race. No more the drudge and idler — ten that toil where one reposes, But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses! |

The poem was later set to music and sung as a protest song in the 1970s. Although it commemorates a long-forgotten episode in labor history, the song has become an anthem of sorts, especially for the rights of working women in America and all around the world.

Here is that song as sung by Judy Collins: