by Nomad

Russia's English-language daily newspaper, The Moscow Times, has this insight in how the Russian government, with state-owned media at its side, is using controversial legislation to intimidate NGOs and hush dissent.

Russia's English-language daily newspaper, The Moscow Times, has this insight in how the Russian government, with state-owned media at its side, is using controversial legislation to intimidate NGOs and hush dissent.

Human rights activist Nadezhda Kutepova had spent decades fighting for the rights residents of Ozyorsk in the Chelyabinsk region, some 600 miles south of Moscow. Today, however, Kutepova is living in Paris. She fears retaliation by Russian authorities if she ever dares to return.

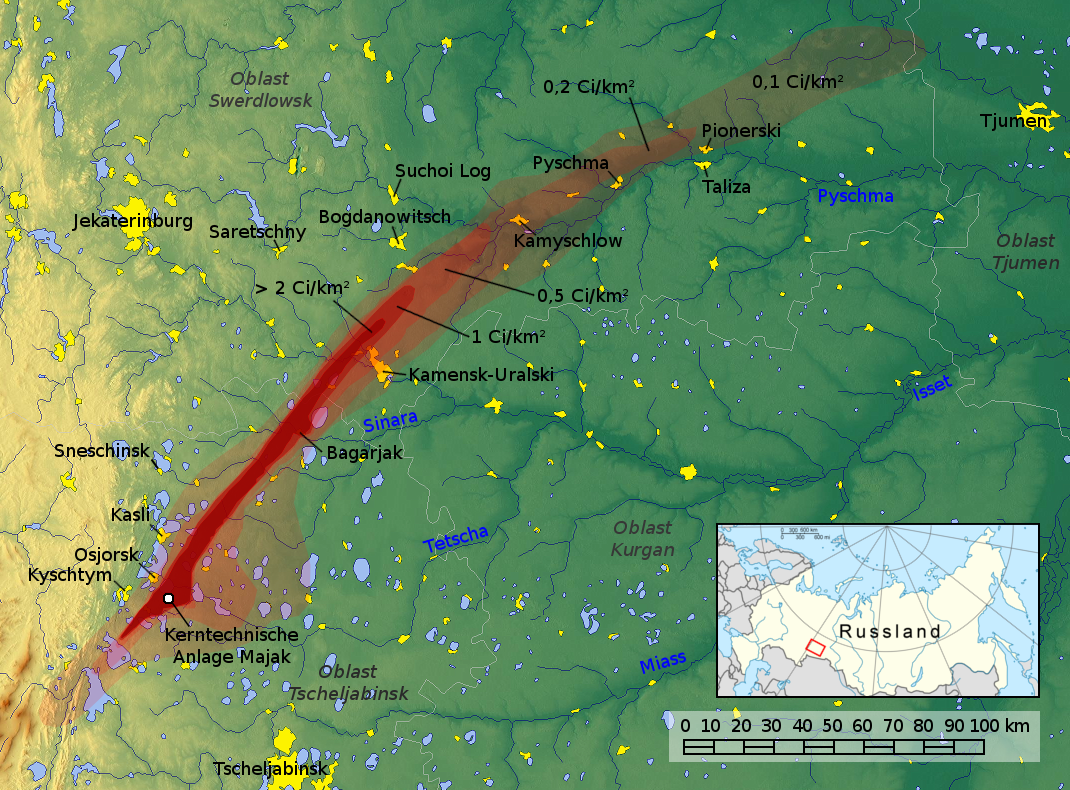

Kutepova used to live in the Ozyorsk area. The region was the scene of one of the worst nuclear accidents at the time, rivaling Chernobyl disaster of 1986, and the third most serious nuclear accident ever recorded. In 1957, one of the storage facilities at the Mayak nuclear plant exploded, scattering radioactive poison in and around the strategic facility and included the Techa River.

It had been a plutonium production site for nuclear weapons and nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in the Soviet Union.

By Kutepova's reckoning, there are around 25,000 people affected by radiation in Ozyorsk and areas surrounding the facility, She believes that some 600,000-700,000 people living in closed towns in Russia whose rights are constantly violated.

A closed town is an area where specific authorization is required to visit or remain overnight. There are currently 44 publicly acknowledged closed cities in Russia with a total population of about 1.5 million people. It is an effective means of maintaining security and, as in this case, keeping things covered-up.

Eventually an accident on this scale could not be completely hidden. The effects on human health are still showing up over half a century later.

Another source provides more details on the effects of the accident:

Untold numbers of people from the region have since died of leukemia, lymph node cancer, and other maladies caused by the widespread contamination. Now classified as a Level Six disaster on the International Nuclear Event Scale, the catastrophic event was kept secret until 1992.

After losing a number of close family members to radiation-related diseases, Ms. Kutepova felt she owed it to the people who lived there to demand compensation from federal authorities.

She founded a non-governmental organization (NGO) in the late '90s called Planeta Nadezhd, translated in English, Planet of Hopes. Its mission was to get treatments and benefits for local residents.

Planet Hope has entered into partnerships with international activist groups and environmental organizations, has created a victims parliament, and facilitates for people across the Urals access to specialist radiation knowledge. Despite intimidation from authorities, the group has conducted analyses of probes from the prohibited zone, as well as taken its protests for justice, openness, and human rights to Moscow's Red Square.

Somewhere along the lines, her NGO clearly ruffled some feathers. As another source reports, in spring of this year, the state, at what level isn't clear, began a campaign to silence her and her organization permanently.

The Foreign Agent Label

The Russian parliament provided the perfect tools to quash unruly organizations.

The Russian parliament provided the perfect tools to quash unruly organizations.

When Planeta Nadezhd did not register as a foreign agent, a local court fined the group, 300,000 rubles ($4,600). That was money that the organization simply didn't have and Kutepova was forced to liquidate the group.

The term "foreign agent"-(Иностранный агент) in Russian- conjures up has strong associations with cold war-era espionage. In the minds of a lot of the older generation whose whole lives were lived in fear of the Western threat, the term still has a powerful impact.

To call somebody a "foreign agent" is therefore tantamount to calling them a spy. For that reason, the law has become a formidable weapon against human rights organization inside the country.

To call somebody a "foreign agent" is therefore tantamount to calling them a spy. For that reason, the law has become a formidable weapon against human rights organization inside the country.

The UK Guardian reports that there are currently 55 Russian NGOs that have been added to the foreign agent blacklist, including Citizens’ Watch, a human rights group, the Human Rights Resource Centre and the Committee Against Torture. Six Russian organisations have been forced by the laws to shut down operations to avoid criminal prosecutions for repeatedly violating the law.

Organizations designated as foreign agents must make all of their publications and must begin each oral statement with a disclosure that the information is derived from a foreign agent. Through increases registration barriers, the law also limits the way a foreign organization can make tax-exempt donations to specific people or the NGO by requiring them to apply and be placed on a very limited list of approved organizations.

In addition, the new regulations place restrictions on foreigners and stateless peoples from establishing or even participating in the organization. A NGO must then submit to extensive audits. Supervisory powers are allowed to intervene and interrupt the internal affairs of the NGO with suspensions for up to 6 months.

Critics to the law also point out that when officials have raided NGOs, the police have been accompanied by television crews from state TV channels.

Grigory Melkonyants explains that accepting the term means “you’re persecuted as a national traitor.” Melkonyants works with the only independent election watchdog in Russia. That organization was the first NGO added to the list of foreign agents in 2013. Said another NGO director

“We’re being punished for providing a podium for people the government doesn’t like, providing a floor for those who are blacklisted.”

Putin's Other Weapon

The day after Planeta Nadezhd was fined. the government-owned Russian TV channel Rossia 1 made her the subject of a five-minute expose on its evening news to Kutepova. The reporter Olga Skabeyeva claimed in the segment that Planeta Nadezhd was using American funds to conduct industrial espionage.

That was only the beginning.

Local newspaper articles began circulating comments from the administration of Ozersk – which is made up of former FSB officers – hinted they would like to see her charged with espionage and treason.

In June, another film about Kutepova was aired on the Yekaterinburg TV channel Rezonans TV. In that report, a former government official charged that Kutepova was trying to close the facility.

He also insinuated that she was doing this at the behest of Western countries and competitors." He added, "Without a doubt, her actions are a threat."

When the government-owned Russian TV channel claiming that her organization was involved in industrial espionage and was plotting against the country's nuclear industry.

Fearing she would be charged with espionage and treason, after consulting with her lawyer — who told her an arrest was highly likely — Kutepova and her four children left for Paris.

According to her lawyer, even the use of the term "espionage" was considered an alarm bell for a possible arrest.

Another source notes that Kutepova represents the first known case where the possibility of charging an NGO leader with treason and espionage has been considered.

Slander and the Control of the Facts

As far as using the media as a weapon, the Moscow Times article points out, that this case is not unique. In the past, state-run media has been employed to attack figures and accuse them of working for foreign governments or corporations.

In one example, the state-run media was used to slander a dead accountant, Sergei Magnitsky, in the sensational Bill Browder affair, (which we have covered in the past.)

The Atlantic Monthly in April (about the same time as Kutepova first ran into trouble) ran a story on Russian president Putin's strategic use of the media as a means of control.

As a former KGB officer and head of the KGB’s successor agency, the FSB, Putin knows the value of information. His concept of the media, however, is a far cry from the First Amendment. For him, it’s a simple transactional equation: Whoever owns the media controls what it says.

And from the start, Putin put that idea into real terms.

From his first days as president, Putin moved quickly to dominate the media landscape in Russia, putting not only state media but privately owned broadcast media under the Kremlin’s influence.

In the Atlantic article, Alexey Venediktov, editor in chief of Echo of Moscow, (Эхо Москвы) explained how Putin views the media as a weapon for the state.

“Here’s an owner, they have their own politics, and for them it’s an instrument. The government also is an owner and the media that belong to the government must carry out our instructions. And media that belong to private businessmen, they follow their orders. Look at [Rupert] Murdoch. Whatever he says, will be.”

Pragmatic Putin may have a point but like a lot of autocrats, Putin has made a cynical rule from the most extreme examples he could find in the West.

After all, much to the chargin of many on the Left, Fox News escapes regulatory control by claiming its First amendment rights which protects both the freedom of speech and of the press.

And yet, praxadoxically, under Putin, Fox News serves as a model for the government media to accuse and intimidate and to assist in shutting down free speech and silencing dissent.

Kutepova has said that she would like to return to Russia and to continue her work. Presently however she has received the status of a petitioner for political asylum in Paris.

Despite her fears and her lawyer's warning, others are not so sure that Russian officials were ever planning to go quite as far as that. Said Alexei Sevastyanov, a regional human rights arbitrator:

"The TV programs were obviously ordered by someone who wasn't pleased with Nadezhda's efforts, But there is no interest from the law enforcement agencies — her organization did receive foreign financing, and in a closed town it was thoroughly inspected, so if there had been any questions, they would have been asked by now,"

Yet the intention was only to itimidate activists and NGOs, then it was a clear success. Kutepova, the mother of four children, couldn't take the risk of losing her freedom.

Either way, the Russian officials got what they wanted.

Control and the silencing of all other voices but their own.

Control and the silencing of all other voices but their own.