by Nomad

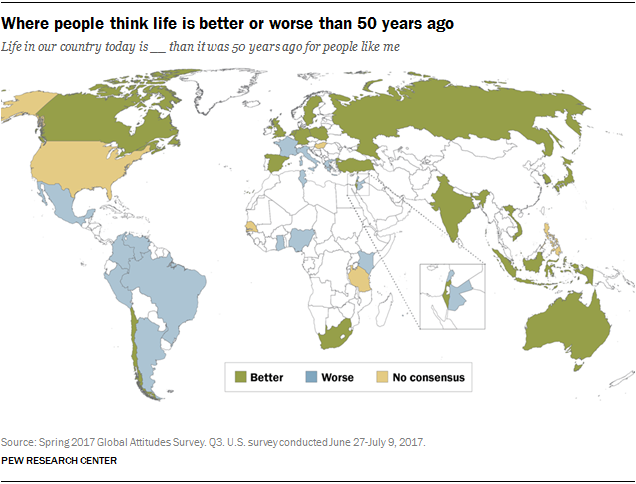

According to a Pew Research study, most of the world's population has mixed feelings when it comes to the advancement made in the last 50 years. Polling nearly 43,000 people in 38 countries around the globe, respondents were asked a simple question: Do you think life is better now than a half-century ago?

Nearly every society has seen dramatic economic growth since the late 1960s. For the majority of nations, this appears to be the most important aspect of improvement. Were people like me doing better financially back then than they are now?

In countries where the current economic mood is positive, people are much more likely to say life is better than it was a half-century ago. This was true even when controlling for the demographic factors of income, education, gender, and age.

The most enthusiastic positive response- not surprisingly- came from

In the top three, the study confirms that economic development in formerly impoverished nations has made the life better- at least, in the eyes of the public.

Nothing astonishing there.

Yet there were some interesting questions on the list of the top ten. Large jumps in the standard of living do not explain why people in more developed nations like

Many respondents from other nations had serious doubts on the question. Half of the Russians polled said life was better, compared to 28% who disagreed.

When asked if life today is better, Americans- as always- were divided but tended overall to think things had not improved very much. Forty-one percent declared life was worse than in the late 1960s while 37% said things are presently better.

When asked if life today is better, Americans- as always- were divided but tended overall to think things had not improved very much. Forty-one percent declared life was worse than in the late 1960s while 37% said things are presently better. But the

In fact, those figures come very close to the global averages.

Other nations were much more pessimistic about a half-century of progress.

Meanwhile, half or more in countries ranging from Italy (50%) and Greece (53%) to Nigeria (54%) and Kenya (53%) to Venezuela (72%) and Mexico (68%) say life is worse today.

Here's the list of nations and percentages.

There's actually a lot going on with this rather simple question. To fully understand the positive or negative results, one has to consider a lot of factors particular to the individual countries. How far have certain countries come when it comes to progress? China and Turkey have come an extraordinarily long way in a relatively short time.

What was going on 50 years ago in that country? For instance, the end of the Cold War was definitely a game-changer. Many countries saw a surge of economic growth and an improvement of living standards following the fall of the Soviet bloc.

In Israel, 52% said things were better, but then in the late 1960s, Israel was facing a fight for survival in its so-called Six-Day War. The same is true, of course, for Vietnam which benefited by both the end of the war with the US and the success of a controlled experiment with capitalism.

In Israel, 52% said things were better, but then in the late 1960s, Israel was facing a fight for survival in its so-called Six-Day War. The same is true, of course, for Vietnam which benefited by both the end of the war with the US and the success of a controlled experiment with capitalism.

A Global View

Regionally, there were also some significant findings. Of all the areas of the world, the most depressed about progress can be found in South America.

Latin Americans stand out for their widespread negative assessment of progress over the past half-century. Venezuelans and Mexicans (72% and 68% life is worse) are the most downbeat, but nowhere in the region do more than half say life has improved for people like themselves.

In other areas, such as the Middle East and North Africa, no particular pattern could be found. Meaning, the view of advancement varied substantially by country.

Turkey reports the most progress in the region, with 65% saying life is better, followed by Israel, where 52% say the same about their country. Tunisians, Jordanians and Lebanese tend to say life has gotten worse for people like them, with Tunisians expressing the most widespread negativity (60%).

Europeans tended to be upbeat but, averaging it out, not by all that much. A regional median of 53% describes life as better today, compared with 30% who take the opposite view.

Beyond Economics

Another thing that analysis suggested: in more than half the countries polled, people with more education say that life is better than it was a half-century ago. The more education a nation offers, the most positive the view of progress.

In general, age did not seem to play a factor in the attitudes about the last 50-years. That said, in some countries, there was a marked difference in opinions according to age groups.

For example in the UK, a full 66% of the 18-29 age group said that life was better today. However, only 41% of the 50 and older agreed.

That pattern could be found in countries like Australia, Sweden, the U.S. and Germany among advanced economies, and in South Africa, Ghana and Peru among emerging economies.

Somewhat related to that is the subject of nostalgia is the rise of right-wing populism. Pew noted that this form of resurgent populism is generally associated with nostalgia for an idealized past.

In the case of Europe, the survey findings confirm that populists tend to be "more enamored of the past than people who look askance at some of the continent’s right-wing populist parties."

For this group, there was no question that things are worse off now.

This factor was not limited to Europe. In lesser degrees, it could be seen in the US and Russia too. Trump's campaign famously played upon the idea of "making America great again" or returning America to a better time in the past. Putin's Russia has also made use of a nostalgia for a Soviet glory that never actually existed. In each of these cases, political supremacy was based on a presumption that things are much worse today and that the only way to a brighter future is to return to a largely-imaginary past.

In theory, this view will depend on the economic success of the populist leader. Once in power, the populist leader faces the dilemma of reversing that view. That is to say, he must show his supporters that things are economically better under his rule than at any time beforehand.

The "I've Got Mine" Factor

The analysis also suggests that in a few countries, perceptions were based on the gains and losses of particular groups, causing sharp divisions along religious or ethnic lines. Take Turkey as one example.

In Turkey, 79% of Muslims who observe the five daily prayers (salah) that are required under Islam say life is better for people like them compared with 50 years ago.

In Turkey, 79% of Muslims who observe the five daily prayers (salah) that are required under Islam say life is better for people like them compared with 50 years ago.

In contrast, only about half (49%) of Turkish Muslims who pray seldom or never at all see the same progress. Is that suggesting that devout Muslims were less than honest in their replies? Not quite, it might reflect, say Pew researchers, the more limited gains made by supporters of the Islamist ruling party in Turkey.

The same thing can be seen in other countries. In Israel, Israeli Jews are much more satisfied with the gains made in the last 50-years than your average Israeli Arab. Nearly six-in-ten Jews in Israel say life has improved, compared with only a third of Israeli Arabs who see similar progress.

It goes beyond religious affiliation. There were also questions of race.

In Turkey, 79% of Muslims who observe the five daily prayers (salah) that are required under Islam say life is better for people like them compared with 50 years ago.

In Turkey, 79% of Muslims who observe the five daily prayers (salah) that are required under Islam say life is better for people like them compared with 50 years ago.In contrast, only about half (49%) of Turkish Muslims who pray seldom or never at all see the same progress. Is that suggesting that devout Muslims were less than honest in their replies? Not quite, it might reflect, say Pew researchers, the more limited gains made by supporters of the Islamist ruling party in Turkey.

It goes beyond religious affiliation. There were also questions of race.

In South Africa, there is a sharp racial divide on social progress: Blacks in the country, who a half-century ago were oppressed via the apartheid system, are much more likely to say life is better today for people like them (52%), compared with mixed-race (or “coloured”) and white South Africans (37% and 27%, respectively).

In this selected group, the view of progress seemed dependent on a very limited view of what progress means and how widely the benefits are dispersed.

What does Progress Mean?

Before we can ever answer this seemly-innocuous question of whether life is better or worse now, we have to examine our definitions of progress and advancement.

What does this concept really mean? In the study, respondents were left to define it for themselves which may, in part, account for some of the conflicting results.

The usual definition of progress is that improvements in the human condition produced by advances in technology, science, and social organization.

When it comes to science, this description opens its own can of worms. For example, is a cell telephone as important an advancement than a cure for malaria? Were advancements in science always an improvement? What about the atomic bomb and long-range missile technology? What about the science of nerve gas and biological weapons?

There are more benign examples too. Comparatively, were the moon landings more significant, in terms of effects on the human condition than, say, the discovery of DNA?

When it comes to science, this description opens its own can of worms. For example, is a cell telephone as important an advancement than a cure for malaria? Were advancements in science always an improvement? What about the atomic bomb and long-range missile technology? What about the science of nerve gas and biological weapons?

There are more benign examples too. Comparatively, were the moon landings more significant, in terms of effects on the human condition than, say, the discovery of DNA?

In terms of social organization, there are also questions, does socialism advance the quality of life more than capitalism? Does secularism lead to more advancement or does it restrict religious expression?

The concept of Progress is very much a product of Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century. Progress, until very recently, was the primary ethos of the American experiment. Stale Europe seemed as uninspiring as curdled milk compared to the robust United States.

Our success, we were told, was based on faith in our principles and one of those principles was an overriding faith that things were steadily getting better. Furthermore, it was an idea that we believed was worth exporting to other nations. To call this conviction into question was considered unnecessarily pessimistic and practically un-American.

Today, if this research is anything to go by, Americans have become much more doubtful about the premise of progress.

What do you think?

- Are things better now than they were fifty years ago, in your opinion? In what way?

- Considering any particular category you wish, (science, social issues or politics) what has been the most significant advancement in the last half-century?

- Do you consider yourself more optimistic or pessimistic in general when it comes to the next 50 years?